Plant Science &

Conservation

Garden Stories

How scientists are rethinking lawns—and how you can, too

For many homeowners, a long, hot summer means mow the lawn, water, repeat. It’s a cycle that feels inevitable if you don’t want a brown, unruly patch of land.

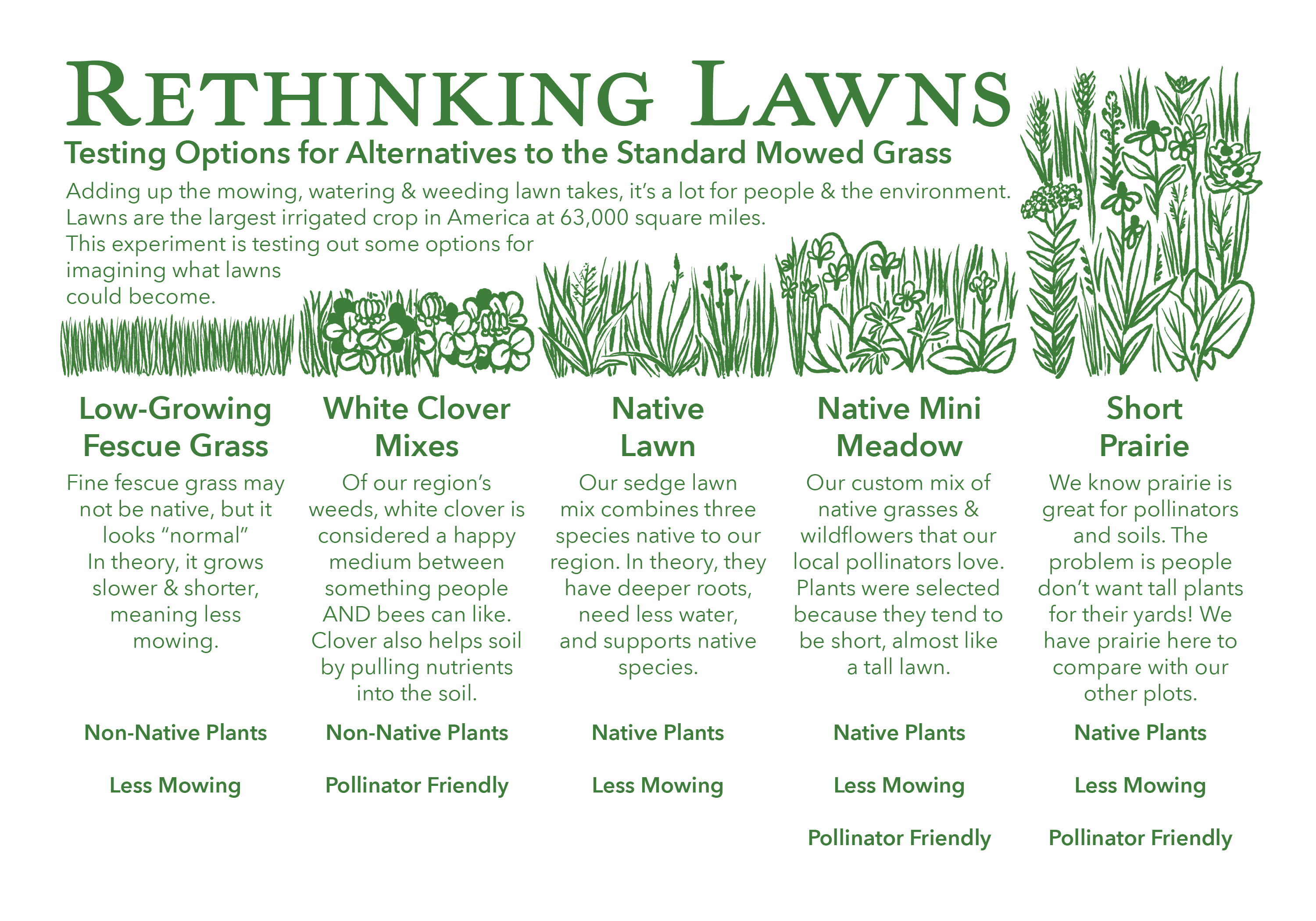

Conservation scientist Becky Barak, Ph.D., is looking to change that assumption. By studying alternatives to traditional turfgrass, she and her collaborators are hoping to offer a “menu of options” for greener lawns that not only look good and stand up well against the Chicago area's moody seasons, but also have positive ecological implications.

The team will also judge how well each option benefits the environment. Pollinator observations will determine how supportive each plot is to bees and other pollinator species. Soil samples will test for carbon storage; more carbon absorption means healthier soil, not to mention more carbon removed from the air. The team will also monitor plant cover in each plot, watching which species do well and spread. “When you look at regular grass, there’s not a lot of bare ground,” Barak said. “We’re thinking about that too.”

Since the alternatives in this study are better suited to Chicago’s climate and habitats, they’re better able to thrive independently. This means less mowing, less water use, and fewer chemical treatments—plus an increase in aesthetically pleasing guests like butterflies. There’s a lot to look forward to.

“Traditional grass lawns dominate the cities, suburbs, and exurbs of our country, which makes the potential impact of this work enormous,” said Kay Havens, Ph.D., Chief Scientist and Negaunee Vice President of Science at the Chicago Botanic Garden. “Each converted lawn uses fewer resources while increasing insect and bird habitat, carbon sequestration, and more. It is hard to imagine just how beneficial this switch could be.”

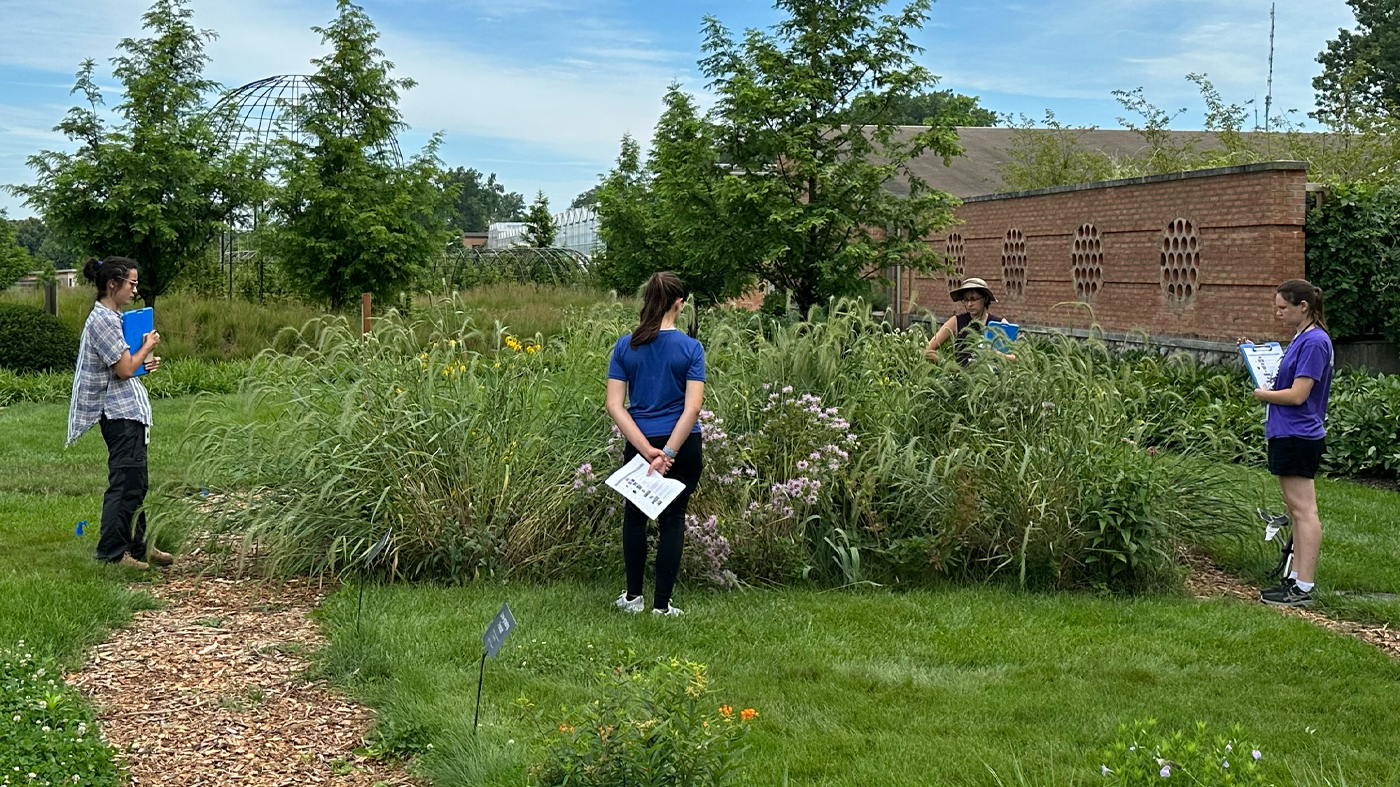

Multiple students in the joint graduate program in plant biology and conservation through Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden have served as research assistants working on the experimental plots, and to date, two students have written their masters theses on data collected with this project.

Barak’s research has garnered excitement not just from conservation scientists, but from horticulture, collections, and natural areas staff at the Garden, who offered advice on growing methods and plant options and helped with the practical issues of preparing and caring for the garden plots. Working with interpretation and design allowed for signage—featuring Kozik’s art—that explains the goals of the experiment and the layout of the plots. While much of the communication on this topic appeals to homeowners, this study partners with horticulturists and land managers that could implement the new ideas on public lands, allowing the impact of the study to scale up quickly. Partnering with the Chicago Park District also means the results can be implemented directly on a large scale.

Visitors to the Chicago Botanic Garden can see the experimental plots growing just south of the Mitsuzo and Kyoko Shida Evaluation Garden. Barak’s team will be looking for public feedback: “What people like, what they don’t like, what they can see potentially using or would like to have in a park near their house,” Barak said. “[This research is] only helpful to the extent that it’s used!”

Visit Rethinking Lawns

—a website designed by Kozik in collaboration with Barak, Tonietto, and Umek—to learn more.

Illustration courtesy of Liz Anna Kozik. View a larger version.