Got Pawpaw?

The rock star fruit is trending

—with fans, chefs, and researchers alike

“It was pretty amazing,” said Susan Strickler, Ph.D., associate conservation genomics scientist at the Chicago Botanic Garden. “It’s really cool to see how there’s a cult-like following for this plant.”

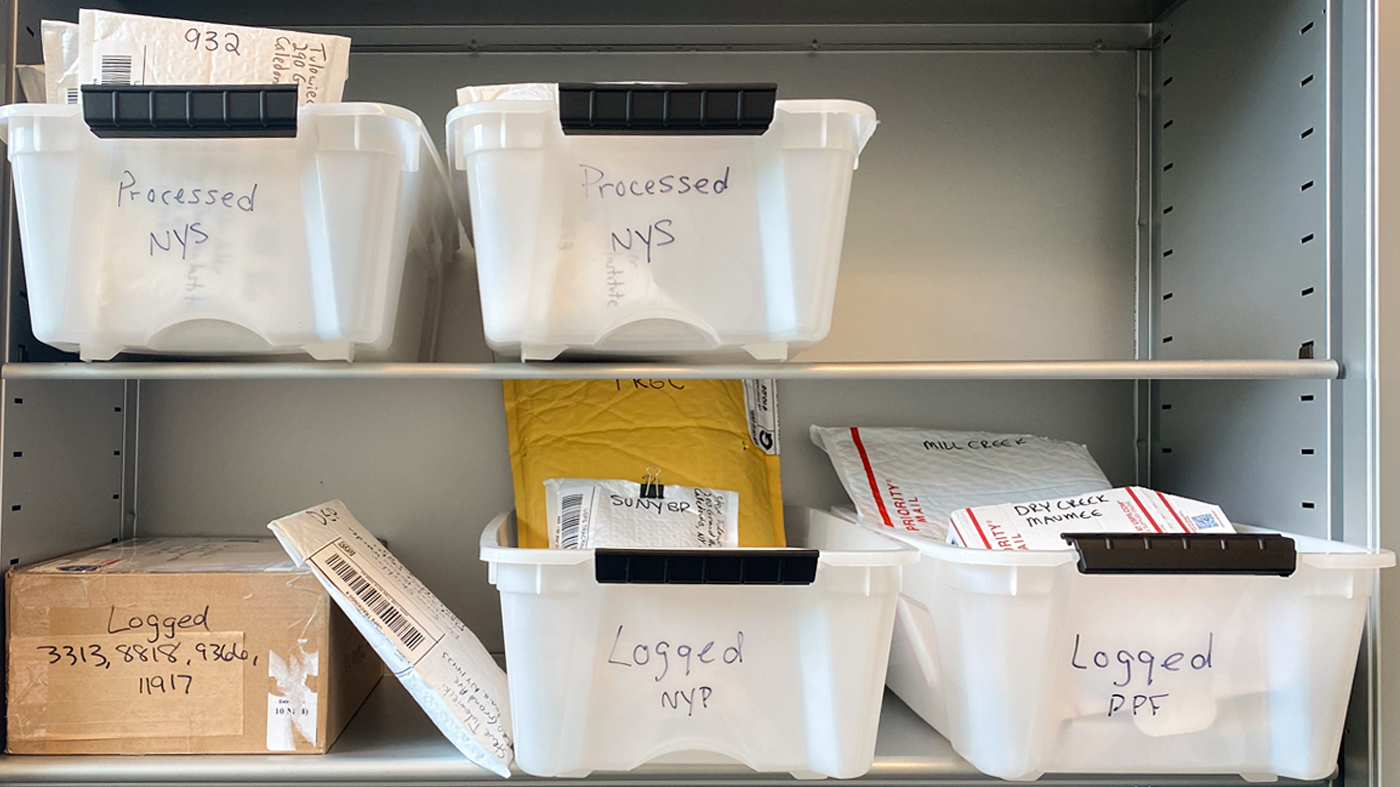

The scientist’s mail bins overflowed with leaves of native pawpaw trees. People had sent hundreds and hundreds of samples from around the country—hoping to help make pawpaw a rock star fruit in local markets everywhere.

Dr. Strickler’s team and collaborators had posted on Facebook, soliciting leaves of Asimina triloba, common pawpaw, from trees in the United States. Many of the 1,000-plus samples came from the Facebook group, Pawpaw Fanatics, which has more than 18,000 members from around the world.

Researchers will extract DNA from the samples to help them determine how the trees have adapted to cold temperatures—other plants that pawpaw is related to grow in tropical climates. The DNA will help the team evaluate pawpaw’s potential as a commercial fruit crop and determine whether the trees can be grown more widely.

The plant has been around for millions of years, and has been used for centuries by Native Americans and others as food and medicine. It’s part of a family of plants that includes tropical fruits such as cherimoya and sugar apples—but pawpaw is the only species in the family that can grow as far north as Ontario, Canada.

The fruit, about the size of a mango, tastes like a mix of pineapple, mango, and banana. You can cut it open and scoop out the pulp with a spoon, avoiding the seeds. It’s good in ice cream and quick breads, and can be used to brew beer and mead.

Serious Eats, the food and drink website, recently wrote an article headlined: “Pawpaws: America’s Best Secret Fruit.” Ohio and other states hold pawpaw festivals. The Inn at Little Washington, a three-star Michelin restaurant in Virginia, has a pawpaw hot drink on its menu.

So what’s not to like? You have to eat, use, or freeze the fruit within a couple days of harvest or they’re no good. That means, the plant has to be grown locally since there’s no good way of shipping them.

It’s hard to find pawpaw fruit for sale locally, but a farmers’ market might have them. Or you can grow the trees in the Chicago area in full sun or light shade and well-drained soil (if you amend the soil with compost). The trees have lovely fall color.

The trees are common in Appalachia but can be found as far west as eastern Nebraska. Learn more about the pawpaw growing range, visit the related Plant Information page.

“It will be interesting to see where our research goes,” Strickler said, “but we know that the community science approach really worked for us. It was great to see so many people who wanted to help out with pawpaw research.”

Calling all pawpaw people

Do you have wild pawpaw trees—not cultivated ones that you planted—on your property in the United States?

If so, and if you want to help pawpaws reach a larger audience, Dr. Strickler’s team would love your help with this research project. Please follow these simple guidelines:

Gather a leaf or two—preferably, a young leaf—from a pawpaw tree.

Put the leaf in a standard-sized envelope with a silica bead packet (the kind marked “do not eat” in some packaged food).

Note the GPS coordinates of your pawpaw tree and include the information in the envelope.

Mail the envelope to the following address: (Note: This project is ongoing, so there is no deadline.)

Dr. Susan Strickler

Chicago Botanic Garden

Plant Conservation Science Center

1000 Lake Cook Rd.,Glencoe, IL 60022

If you'd like a custom-designed pawpaw sticker as a token of our appreciation, please enclose a self-addressed stamped standard-sized envelope. Otherwise, thanks in advance for your participation.

All photos courtesy of Susan Strickler, Ph.D., except for the one of her, shot by Robin Carlson.