A Comparative Evaluation of Ironweeds (Vernonia spp.)

A Comparative Evaluation of Ironweeds

(Vernonia spp.) | Issue 45 2020

Richard G. Hawke, Plant Evaluation Manager and Associate Scientist

Vernonia gigantea

Ironweeds inhabit a broad swath of the United States, from the mid-Atlantic to the Midwest and from Minnesota south to Texas. While many are tall, even towering in height, all ironweeds offer an abundance of purple-hued flowers in late summer and early fall. Their value as a food source for pollinators is irrefutable—scores of bees, butterflies, and numerous other insects feverishly work the flowers throughout the late bloom season. Ironweeds are extraordinary ecological plants, due to their indigenousness and importance as powerhouse pollinator plants, but they are great garden plants too. At a glance, some ironweeds may seem too tall for many gardens, but recent breeding has resulted in a number of compact hybrid selections. The shorter ironweeds may have given up some size but have lost none of their ornamental appeal or draw for pollinators.

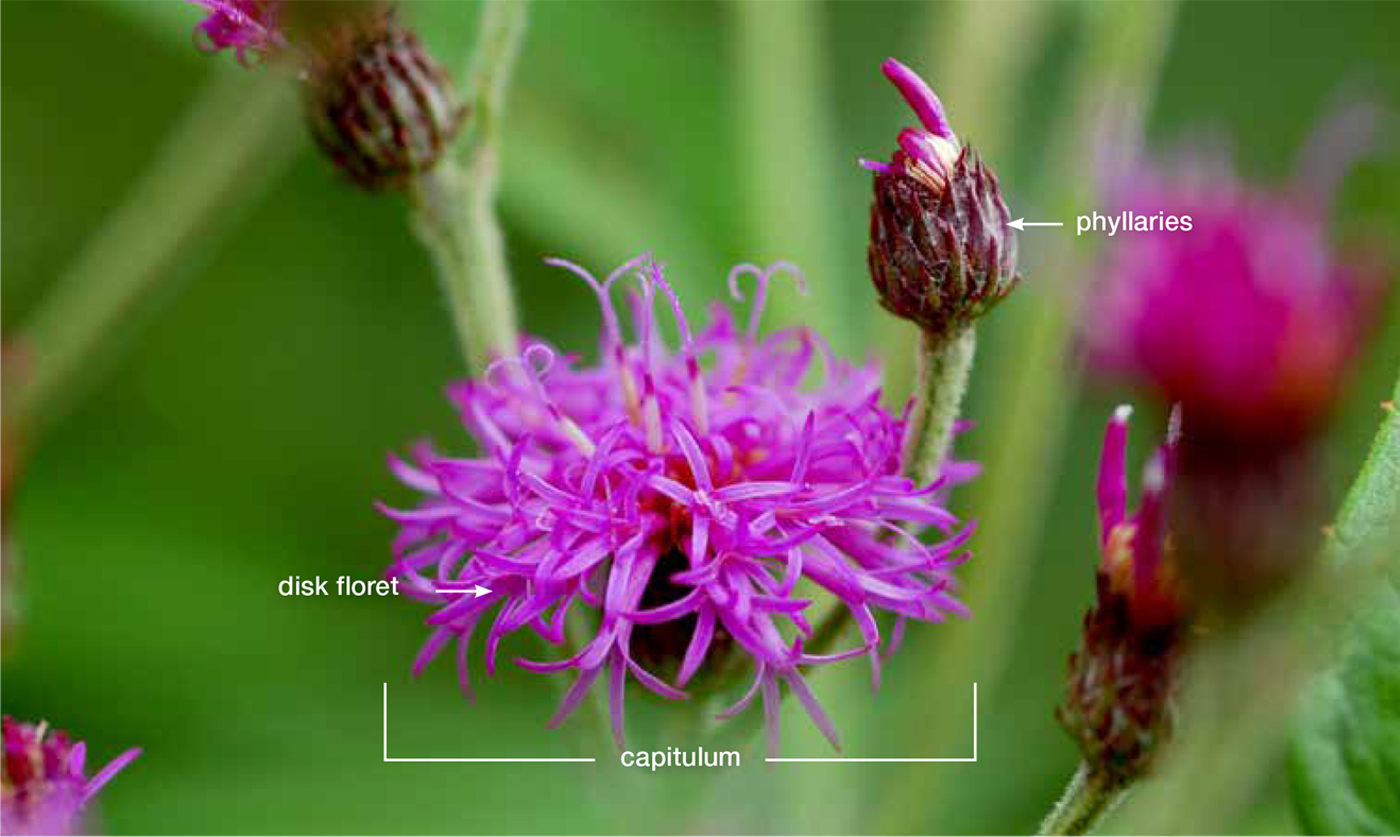

Vernonia spp. are in the aster or daisy family (Asteraceae), but lack the showier petal-like ray florets common to the composite inflorescences of coneflowers (Echinacea spp.), asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), and sunflowers (Helianthus spp.). Instead, upward of 50 or more small tubular disk florets are crowded into a compact flower head or capitulum, which is surrounded by involucral bracts or phyllaries that are unique to a species and helpful in identification. Phyllaries are made up of whorls of small leaflike structures that encase the flower heads, and may be leafy, spiny, or fringed. For several weeks beginning in mid- to late summer, purple to magenta capitula bloom in many-flowered inflorescences measuring up to a foot or more across. The genus is named for William Vernon (1688-1711), an English botanist who collected plants in Maryland. The common name may be a nod to the iron-like rigidity of the stems, or more likely refers to the cinnamon-colored hairs on the fruit.

Leaves are typically dark green and tend toward lance-shaped but can be willow-like to filiform. Conversely, silver ironweed (Vernonia lindheimeri var. leucophylla) sports bright silvery white linear leaves. Leaf size enhances the robustness of some ironweeds; for example, giant ironweed (V. gigantea) reaches 8 feet tall, but the 10-inch long leaves make it seem even larger. On the other hand, at 3 inches long and barely wider than a sliver, the linear leaves of narrowleaf ironweed (V. lettermannii) look more like Arkansas blue star (Amsonia hubrichtii) than any of its kin. Ironweed leaves may be entirely smooth or hairy on the undersides—the soft fuzziness of Missouri ironweed’s (V. missurica) leaves and stems are a notable case. Most of the commonly cultivated species have woody, fibrous root crowns and stiff stems ranging from several feet to 10 or more feet in height.

Ironweeds are generally easy to grow in full sun and moist, well-drained soils but are often adaptable to light shade and drier soils, and some species are drought-tolerant once established. Silver ironweed, for example, is best grown in lean, gravelly soil or decomposed granite, in full or half-day sun. Ironweeds tend to grow taller in moist conditions. Many ironweeds are hardy to at least USDA Zone 5 or colder, while others are native to warmer places in the Southeast and westward to Texas. Ironweeds are typically long-lived, growing into large clumps over time, but rarely need division. Cutting stems back by half in late spring will reduce the ultimate plant height; while thinning the crowns by selectively removing stems in spring increases air flow through the plant and can help reduce foliar diseases. Deadheading reduces unwanted seedlings, which can be prolifically produced, especially in moist areas; however, deadheading removes a food source for late-season songbirds. Powdery mildew and rust can infect foliage in late summer or fall—some species are more susceptible than others. Disease levels can be severe, thus deleteriously affecting plant health. The bitter-tasting leaves are usually not palatable to most grazing mammals including deer.

Ironweeds are both a boon and a challenge to gardeners—their size can be daunting for average gardens, but their late-blooming purple flowers attract a host of pollinators. Ironweeds put on an impressive show in native and naturalistic landscapes, meadows, and formal gardens. In early summer, the dark green foliage provides a handsome backdrop for a variety of earlier-blooming perennials; whereas, late-season bloomers such as sunflowers (Helianthus spp.), goldenrods (Solidago spp.), and big bluestems (Andropogon gerardii cultivars) make stellar floral companions. A shorter stature and feathery foliage sets narrowleaf ironweed (Vernonia lettermannii) apart from other species, and provides a pleasing textural contrast with bolder plants. Despite the large number of species—upward of 1,000 herbaceous and woody plants from the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia—ironweeds are not widely cultivated and still are uncommon in home gardens.

List of Sections

The Evaluation Study

The Performance Report

Top-rated Panicle Ironweeds

Other Ironweeds in the Trial

Summary and Performance Chart

References

Armitage, A.M. 2008. Herbaceous Perennial Plants, Third Edition. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing L.L.C.

DiSabato-Aust, T. 2006. The Well-Tended Perennial Garden. Portland, OR: Timber Press, Inc.

Gleason, M.L., Daughtrey, M.L., Chase, A.R., Moorman, G.W., and Mueller, D.S. 2009. Diseases of Herbaceous Perennials. St. Paul, MN: APS Press.

Rice, G., editor-in-chief. 2006. American Horticultural Society Encyclopedia of Perennials. New York, NY: DK Publishing, Inc.