An Evaluation Study of Cultivated Knotweeds

An Evaluation Study of Cultivated Knotweeds | Issue 48 2024

Richard G. Hawke, Director of Ornamental Plant Research

Persicaria virginiana

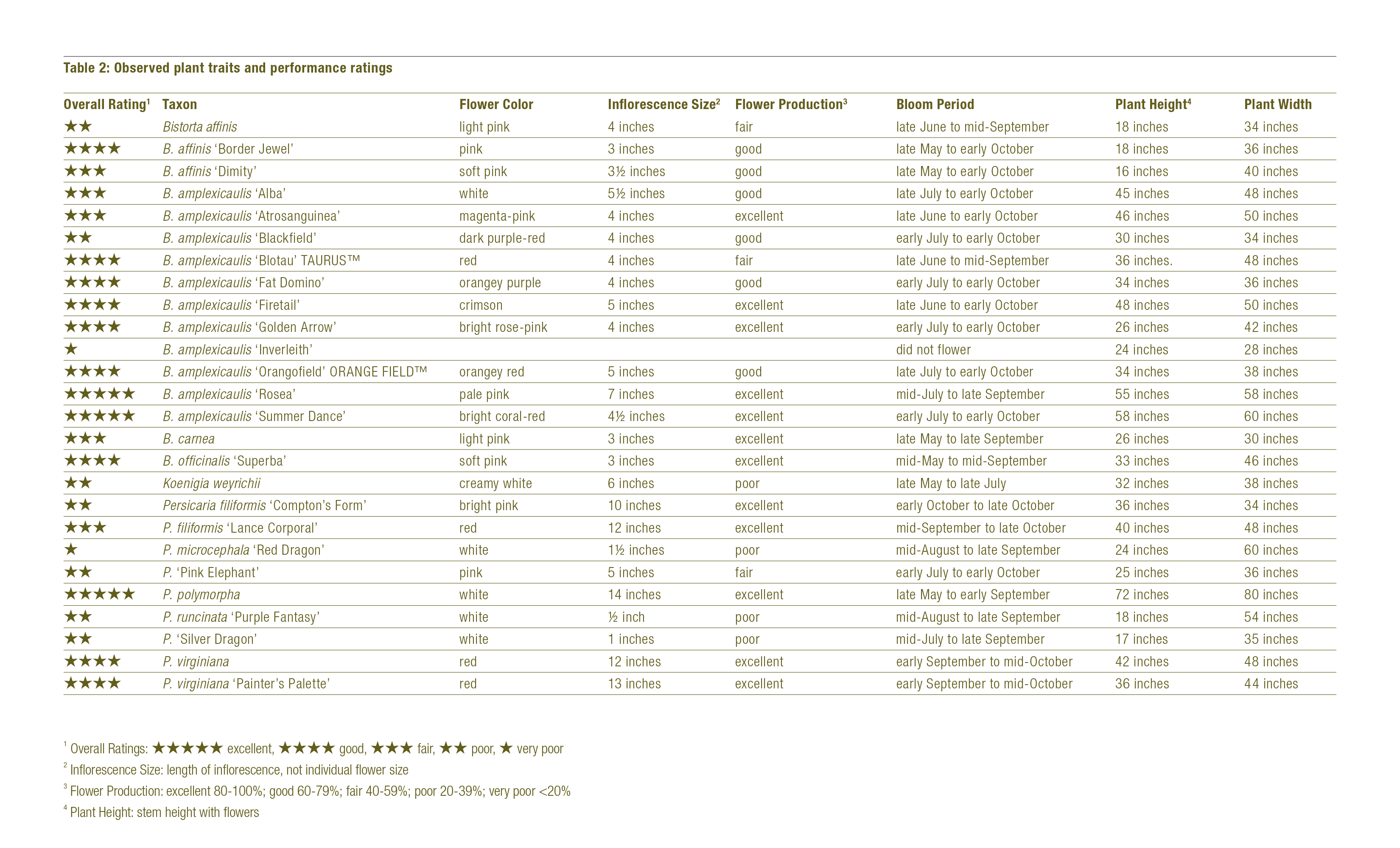

Knotweeds are garden-worthy perennials deserving greater attention. Their wider use in gardens and landscapes may be complicated by the thuggish reputations of certain species. Gardeners should avoid planting any of the weedy or invasive knotweeds, whether native or nonnative, and look to one of the many well-mannered species instead. Cultivated knotweeds offer up a variety of flower colors and forms, leaf shapes and sizes, and plant habits from ground-hugging dwarf fleece flower (Bistorta affinis) to the shrublike white dragon (Persicaria polymorpha).

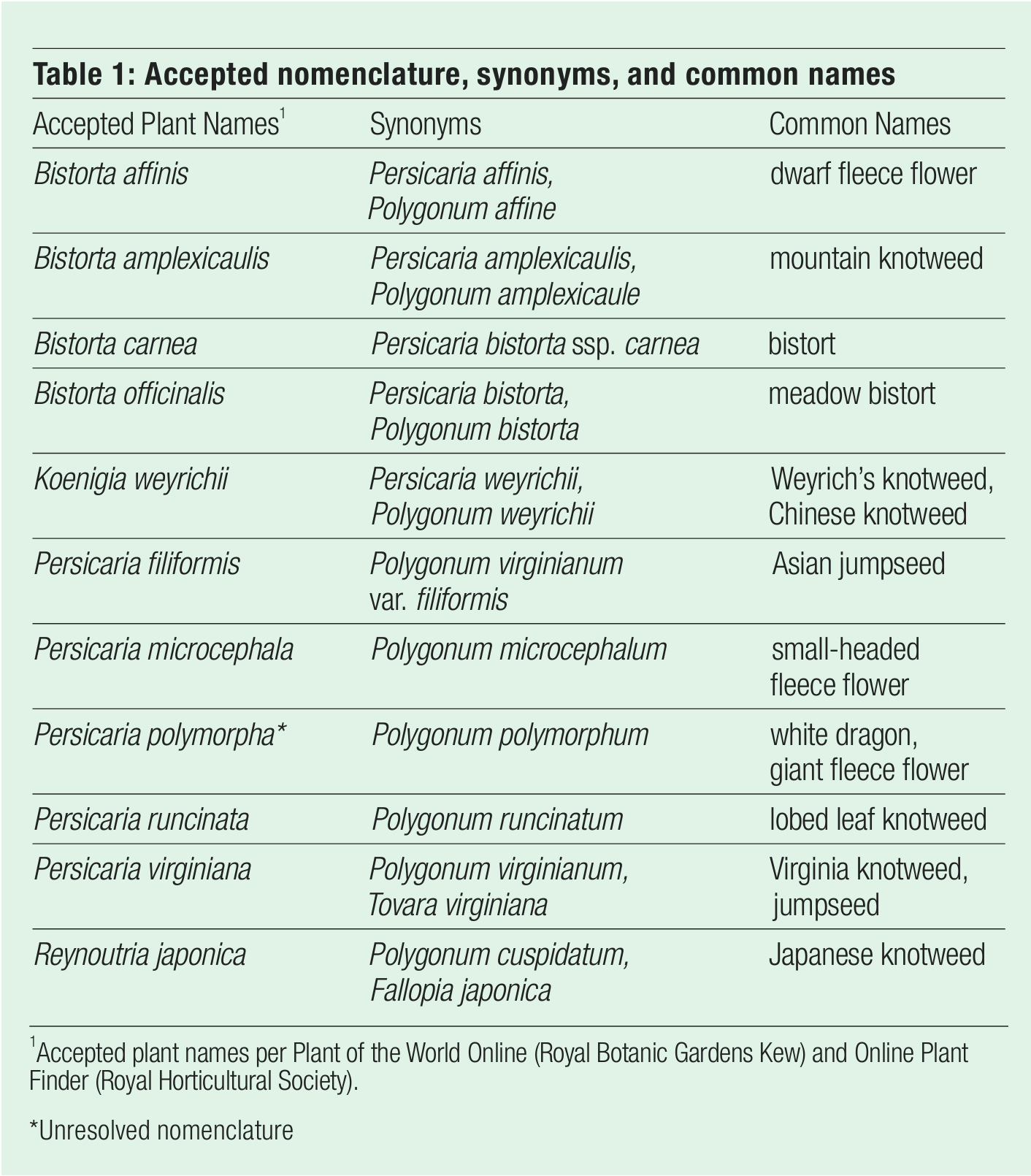

Knotweeds are members of the large buckwheat family (Polygonaceae) and have a worldwide distribution. A variety of botanical and common names are associated with knotweeds. In references and in commerce, Persicaria, Polygonum, Fallopia, Tovara, Bistorta, and Reynoutria are all in use. Nomenclatural changes over the years have created confusion for gardeners (see Table 1 under the Evaluation Study Section below); the time lag between new botanical names being crafted and accepted and ultimately put into general usage can be protracted. Knotweed, fleece flower, jumpseed, and bistort are common names pertaining to one or more species.

In summer and fall, white, pink, red, or purple flowers cluster in terminal spikes or sprays. The tiny bisexual flowers are typically densely clustered in chubby bottlebrushes, on slender wiry wands, or in broad panicles. The bright red beadlike blossoms of Virginia knotweed (Persicaria virginiana) scattered loosely along delicate threadlike spires are an especially distinctive exception. Seedheads may age to russet, bronze, or coppery tones. Seedheads are ornamental on their own but are also showy among remontant flowers late in the season.

Growth forms range from low carpetlike spreaders to large bushy mounds, and are either tap- or fibrous-rooted, and clumping, rhizomatous, or stoloniferous. Leaf shapes may be lanceolate or ovate to hastate or sagittate with long pointed tips. The common name references the swollen stem joint or knot at the base of the leaves. Leaves in shades of green are most common but whitesplashed ‘Painter’s Palette’, silver-and-burgundy ‘Red Dragon’, and radiant-yellow ‘Golden Arrow’ are colorful novelties. Chevrons mark the leaves of some knotweeds, notably the prominent maroon splotches on chartreuse-leaved ‘Lance Corporal’ or the mint-green shadows on ‘Silver Dragon’.

Knotweeds grow best in consistently moist soils in full sun to partial shade. Light shade is essential in warmer zones but even in the north, Virginia knotweed will appreciate afternoon shade and wind protection. While most species are tolerant of periodically soggy sites, they sulk in dry soils. Crispy leaves are an indication of overly dry conditions, too much direct sunlight, or high temperatures. Divide knotweeds in spring or fall as needed to control size and spread. Aggressively rhizomatous knotweeds should be used with caution or avoided regardless of their nativity; self-sowing native species such as Virginia knotweed can also become a nuisance under ideal growing conditions. There are few serious diseases or pests of knotweeds, but Japanese beetles can impact the appearance of the foliage.

Knotweeds are versatile perennials in gardens, naturalized meadows, and in mixed containers, whether in mass or as specimen plants. The low profile and spreading habit of Bistorta affinis ‘Border Jewel’ and ‘Dimity’ make them good choices for massing at the front of a bed, as edging along paths, or fronting shrubs. The hulking size of Persicaria polymorpha can be used successfully as a shrub substitute for hedging. At the Chicago Botanic Garden, a stylized meadow of crimson-spired ‘Firetail’ (B. amplexicaulis ‘Firetail’) nestled in a grassy sea of palm sedge (Carex muskingumensis) highlights the bold traits of the knotweed.

Japanese knotweed

The rampant nature of Japanese knotweed is well-documented and its status as a noxious weed is generally recognized worldwide. Japanese knotweed has escaped or naturalized in all but nine states and in much of Canada and is considered the most pernicious weed in England. So, why undertake a study to determine if it has invasive tendencies? It was not the weedy nature of Japanese knotweed that precipitated the study, but rather the concern that related knotweed species were unfairly compared to it. Japanese knotweed in its wild form was not included in the trial, although commercial sources were surveyed to see if it was offered for sale. No commercial sources were found; however, three cultivars and one natural variety of Japanese knotweed were purchased from mail order nurseries.

Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica, synonyms Polygonum cuspidatum, Fallopia japonica) is an upright shrubby perennial with stout bamboolike stems to 15 feet tall. The green leaves—to 6 inches long—are broadly egg-shaped with pointed tips. Sprays of white flowers crown plants in late summer. As commanding as the plant is above ground, what’s happening underground is startling. A vast network of thick rhizomes can travel up to 60 feet from a plant’s nexus. Japanese knotweed spreads rapidly, forming dense thickets that shade and crowd out native plants, thus threatening natural ecosystems, species diversity, and wildlife habitat. Once established, Japanese knotweed is persistent and difficult to eradicate—shoots can sprout from small rhizome fragments buried up to several feet deep and can punch through asphalt.

Seed dispersal by wind, water, animals, humans, or in soil is cited as a primary mode of spreading Japanese knotweed, yet some references report that seeds are produced but rarely viable. In our trial, weediness or potential invasiveness was measured by the vigorous rhizomatous habits rather than seedlings, which were not observed in or around the plots. Although our study did not confirm seed viability, the invasive status of Japanese knotweed over much of the continent dictates an abundance of caution. While listed as cold-hardy to USDA Zone 5, the fact that it has naturalized in northern tier states, Alaska, and most Canadian provinces implies its adaptability to extreme climates.

During the planning process, no commercial sources were discovered for Japanese knotweed and mail order sources for related varieties and cultivars were scarce. The trial group included Reynoutria japonica var. compacta, R. japonica var. compacta ‘Variegata’, R. japonica ‘Crimson Beauty’, and R. japonica ‘Devon Cream’. All plants were vigorous but remained in their given space for several years before significant movement was noted. ‘Devon Cream’ was the most aggressive selection, spreading over 20 feet in all directions and into the turf by the fourth year. At the same time, greenleaved reversions began overgrowing its taupe-speckled variegation, resulting in greater plant vigor and increased flower production. Upon completion of the trial, plants and rhizomes were dug out manually in spring and the site was kept under close observation for any resprouting, which was minimal that year. Sprouts were promptly removed when discovered the following year; no stems emerged in subsequent years. Japanese knotweed and related selections are on the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Invasive Plant List.

List of Sections

The Evaluation Study

The Evaluation Report

Top-rated Knotweeds

Evaluation Details

Summary and Performance Chart

References

Armitage, A.M. 2020. Herbaceous Perennial Plants, Fourth Edition. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing L.L.C.

Flora of North America Online. floranorthamerica.org.

Rice, G., editor-in-chief. 2006. American Horticultural Society Encyclopedia of Perennials. New York, NY: DK Publishing, Inc.

Botanic Gardens Kew, Plant of the World Online. powo.science.kew.org.

Royal Horticultural Society, Online Plant Finder. rhs.org.uk/plants.