Plant Evaluation: Lavenders for Northern Gardens

Lavenders for Northern Gardens | Issue 42 2017

Richard G. Hawke, Plant Evaluation Manager and Associate Scientist

Lavender trial beds in the Lavin Plant Evaluation Garden.

Lavenders have long been cultivated for their broad herbal and medicinal uses, and are enduringly popular as ornamentals in gardens and landscapes around the world. Famously, bountiful fields of lavender grown for its fragrant oil are the essence of France’s Provence region. Lavender derives from lavare, Latin for “to bathe or wash," because the ancient Romans steeped bundles of this aromatic herb in bathing water. Lavender is familiar in everyday life, giving its distinctive scent and color to a myriad of personal, home, and culinary goods.

Lavenders (Lavandula spp.) are Old World plants, with 28 species native to the Mediterranean region, northern Africa, western Asia, and the Middle East. While technically a subshrub, the woody stems are often injured or killed in cold winters—L. angustifolia, L. xintermedia, and L. xchaytoriae, are typically listed hardy in USDA Zones 6-9. Consequently, lavenders are treated as perennials in areas where stem dieback is the rule rather than the exception. The mild climate of their native range is so unlike the temperate Upper Midwest that growing lavenders may seem impossible. Despite their generally tender aspect and the constraints of their cultural requirements, some lavenders grow successfully in northern regions.

Like other members of the mint family (Lamiaceae), lavenders feature bilabiate or two-lipped flowers arranged in verticillate or whorled clusters on square stems. While its name would imply otherwise, English or common lavender, Lavandula angustifolia, is a native of the Mediterranean region and represented in cultivation by a plethora of cultivars. The small flowers, clustered in six to eight verticillasters, form compact terminal spikes on stiff stems held above the leaves. Flower colors range from shades of lavender or violet to purple, pink, and white, usually with darker or contrasting calyces. All parts of the plant are tomentose and aromatic due to volatile oils in the inflorescences, stems, and leaves. The oppositely paired leaves are generally narrowly lanceshaped, about 2 inches long, silvery to gray-green, and evergreen in mild winters. English lavender has a mounded habit, 12 to 36 inches tall depending on the cultivar, and can grow quite wide with age under ideal conditions.

Lavandin, Lavandula xintermedia, is a natural hybrid of L. angustifolia and L. latifolia, another Mediterranean native. There are only slight differences related to flower size and bloom season between the two species and lavandin cultivars are plentiful, too. Lavandula xchaytoriae, a man-made cross between English lavender and woolly lavender, L. lanata, originated in England in the 1980s. It has the fuzzy silver leaves of woolly lavender and some of the cold hardiness of L. angustifolia.

Lavenders prefer full sun and well-drained to dry, alkaline soils—gravelly or sandy soils are ideal. Good soil drainage, especially in heavier clay soils, is crucial to year-round survival. Maintenance needs are few since lavenders do not require regular irrigation or fertilizer to flourish. Deadheading is the gardeners’ choice but is helpful in keeping plants tidy. Shearing lavenders by one-third after blooming removes spent flower stalks and shapes the plant. Substantial pruning may be necessary on severely winter-damaged plants; cut stems back after new growth begins in the spring. Fungal root rot can be troublesome in poorly drained soils and during periods of heavy rainfall and/or high humidity. Fungal and bacterial leaf spotting, stem blight, and wilt are also possible problems in warm, wet weather. Fourlined plant bugs, caterpillars, and northern knot nematodes are occasional pests. The natural oils in lavenders repel most grazing mammals such as deer and rabbits.

The essential oil of lavender scents perfumes, balms, and soaps; dried lavender sprigs are a staple in potpourris and sachets, as well as flavoring for teas, condiments, and foodstuffs. By most accounts, English lavender yields the finest quality oil; nonetheless, ‘Grosso’ lavandin rather than English lavender is most widely grown for commercial oil production in France. As a garden plant, lavenders of all stripes are exceptional in rustic to traditional landscapes. At home in flower, vegetable, and herb gardens, lavenders fit especially well in rockeries and xeric or waterwise gardens. Lavender is a versatile garden plant, whether as a specimen in a border or pot, massed as a groundcover, or hedged to define a space. The silvery leaves are a wonderful counterpoint to a variety of leaf and flower colors, while the blossoms draw an assortment of pollinators.

Lavender trial beds in the Lavin Plant Evaluation Garden.

List of Sections

The Evaluation Study

The Performance Report

Top-rated Lavenders

Observations

Summary

References

Armitage, A.M. 2008. Herbaceous Perennial Plants, Third Edition. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing L.L.C.

Jones, L. 2008. Hardy Lavenders. RHS Plant Trials and Awards Bulletin. Woking, Surrey, UK: Royal Horticultural Society

Phillips, E. and C.C. Burrell. 2004. Rodale’s Illustrated Encyclopedia of Perennials. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Inc.

Royal Horticultural Society, Online Plant Finder. rhs.org.uk/plants.

The Plant Evaluation Program is supported by the Woman’s Board of the Chicago Horticultural Society and the Searle Research Endowment.

Plant Evaluation Notes© are periodic publications of the Chicago Botanic Garden.

The Chicago Botanic Garden is one of the treasures of the Forest Preserves of Cook County.

-

In June 2010, the Chicago Botanic Garden (USDA Hardiness Zone 5b, AHS Plant Heat-Zone 5) initiated a seven-year lavender trial, which included 40 commercially available selections of Lavandula angustifolia, L. xintermedia, and L. xchaytoriae. The impetus for the trial was a common conception that lavenders were not reliably cold-hardy in USDA Zone 5; the goal was to determine the potential for growing lavenders in northern regions. Beyond chronicling their ornamental attributes, assessments were made on winter hardiness, adaptability to average growing conditions, and longevity in the landscape.

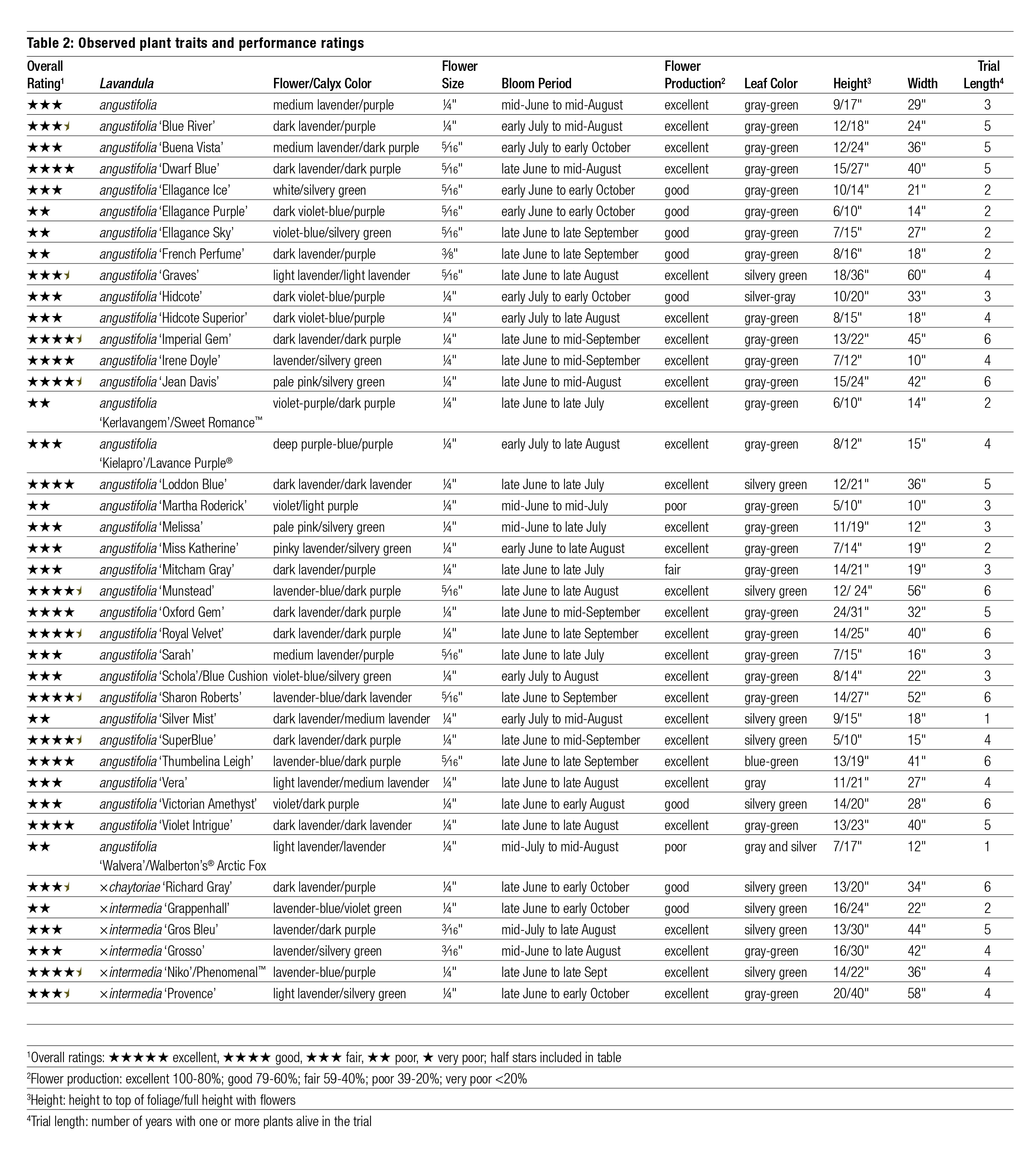

Three plants of each taxon were grown in side-by-side plots for easy comparison of ornamental traits and landscape performance. The evaluation garden was openly exposed to wind in all directions and received at least ten hours of full sun daily during the growing season, which averaged 180 days per year for the 2010–2016 trial period (see Table 1). The clay-loam soil had a pH of 7.4 throughout this period, and although typically well-drained, the soil retained excess moisture for short periods in summer and winter. Trial beds were raised eight inches above the surrounding turf to improve soil drainage.

Maintenance practices were kept to a minimum, thereby allowing the plants to thrive or fail under natural conditions. Trial beds were irrigated via overhead sprinklers as needed, mulched with composted leaves once each summer, and regularly weeded. Moreover, plants were not deadheaded, fertilized, winter mulched, or chemically treated for insect or disease problems. Dead stems were removed each spring after winter injury assessments were completed.

Lavender nomenclature in this report follows the Royal Horticultural Society’s online plant finder as well as other horticultural references. While it was possible to verify most names, a few discrepancies remained unresolved. Most notably, variations of the cultivar and trademark names for Lavandula angustifolia ‘Walvera’ exist in print and on websites, where it is alternately referenced as ‘Silver Edge’, Walberton’s Silver Edge, and Walberton’s® Arctic Fox; we settled on Walberton’s® Arctic Fox for the trial. We also went with Lavance Purple®/L. angustifolia ‘Kielapro’ instead of ‘Lavance Purple’ or ‘L’Avance Purple’. Finally, based on several references to its hybrid traits, we assigned ‘Grappenhall’ to L. xintermedia rather than L. angustifolia, which appears to be an equally prevalent designation.

In June 2010, the Chicago Botanic Garden (USDA Hardiness Zone 5b, AHS Plant Heat-Zone 5) initiated a seven-year lavender trial, which included 40 commercially available selections of Lavandula angustifolia, L. xintermedia, and L. xchaytoriae. The impetus for the trial was a common conception that lavenders were not reliably cold-hardy in USDA Zone 5; the goal was to determine the potential for growing lavenders in northern regions. Beyond chronicling their ornamental attributes, assessments were made on winter hardiness, adaptability to average growing conditions, and longevity in the landscape.

Three plants of each taxon were grown in side-by-side plots for easy comparison of ornamental traits and landscape performance. The evaluation garden was openly exposed to wind in all directions and received at least ten hours of full sun daily during the growing season, which averaged 180 days per year for the 2010–2016 trial period (see Table 1). The clay-loam soil had a pH of 7.4 throughout this period, and although typically well-drained, the soil retained excess moisture for short periods in summer and winter. Trial beds were raised eight inches above the surrounding turf to improve soil drainage.

Maintenance practices were kept to a minimum, thereby allowing the plants to thrive or fail under natural conditions. Trial beds were irrigated via overhead sprinklers as needed, mulched with composted leaves once each summer, and regularly weeded. Moreover, plants were not deadheaded, fertilized, winter mulched, or chemically treated for insect or disease problems. Dead stems were removed each spring after winter injury assessments were completed.

Lavender nomenclature in this report follows the Royal Horticultural Society’s online plant finder as well as other horticultural references. While it was possible to verify most names, a few discrepancies remained unresolved. Most notably, variations of the cultivar and trademark names for Lavandula angustifolia ‘Walvera’ exist in print and on websites, where it is alternately referenced as ‘Silver Edge’, Walberton’s Silver Edge, and Walberton’s® Arctic Fox; we settled on Walberton’s® Arctic Fox for the trial. We also went with Lavance Purple®/L. angustifolia ‘Kielapro’ instead of ‘Lavance Purple’ or ‘L’Avance Purple’. Finally, based on several references to its hybrid traits, we assigned ‘Grappenhall’ to L. xintermedia rather than L. angustifolia, which appears to be an equally prevalent designation.

-

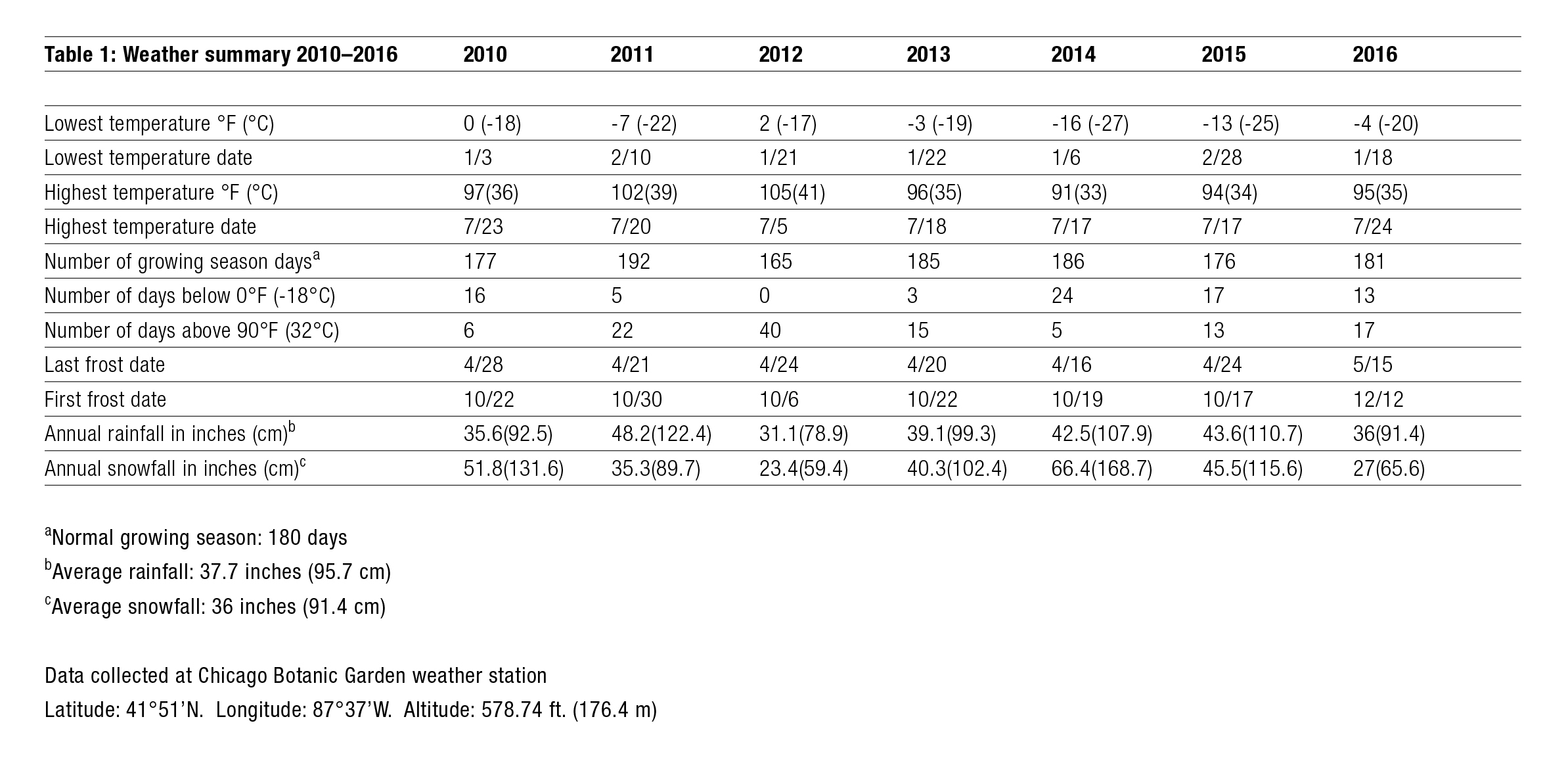

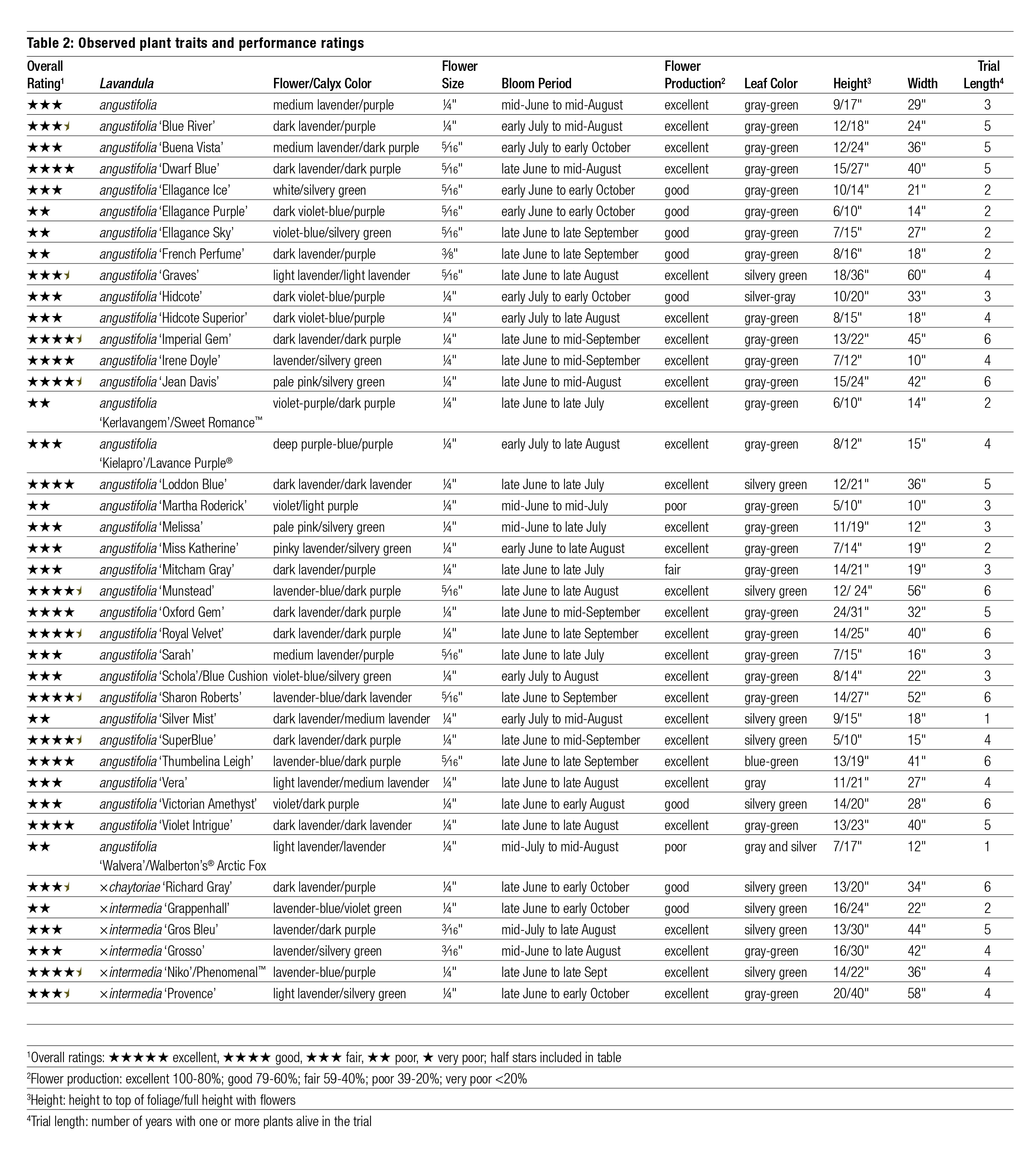

At the start of the lavender trial in June 2010, 19 taxa were planted in the full-sun trial garden. An additional 16 taxa entered the trial in spring 2011; the remaining five taxa were newer commercial introductions when added in 2013 and 2014. In all, 40 lavender taxa were evaluated between June 2010 and November 2016. Twenty- four of the 40 taxa survived four or more winters; 38 taxa lived through two or more winters. Two taxa—‘Walvera’/Walberton’s® Arctic Fox and ‘Silver Mist’—grew for one season but did not survive a winter; ‘Walvera’ was retested with the same results but ‘Silver Mist’ was not replanted. All lavenders were evaluated for cold hardiness; cultural adaptability to the soil and environmental conditions of the trial site; disease and pest problems; and ornamental qualities associated with flowers, foliage, and plant habits. Final performance ratings are based on winter hardiness, flower production, foliage and habit quality, and plant health and vigor. Table 2 shows the observed plant traits and overall ratings for all lavenders, regardless of number of years in the trial.

At the start of the lavender trial in June 2010, 19 taxa were planted in the full-sun trial garden. An additional 16 taxa entered the trial in spring 2011; the remaining five taxa were newer commercial introductions when added in 2013 and 2014. In all, 40 lavender taxa were evaluated between June 2010 and November 2016. Twenty- four of the 40 taxa survived four or more winters; 38 taxa lived through two or more winters. Two taxa—‘Walvera’/Walberton’s® Arctic Fox and ‘Silver Mist’—grew for one season but did not survive a winter; ‘Walvera’ was retested with the same results but ‘Silver Mist’ was not replanted. All lavenders were evaluated for cold hardiness; cultural adaptability to the soil and environmental conditions of the trial site; disease and pest problems; and ornamental qualities associated with flowers, foliage, and plant habits. Final performance ratings are based on winter hardiness, flower production, foliage and habit quality, and plant health and vigor. Table 2 shows the observed plant traits and overall ratings for all lavenders, regardless of number of years in the trial.

-

Seven taxa received the highest ratings for exceptional flower production, healthy foliage, vigorous habits, adaptability to the growing conditions, and superior winter hardiness. Based on cumulative evaluation scores, the top-rated lavenders in descending order were ‘Imperial Gem’, ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Munstead’, ‘SuperBlue’, ‘Jean Davis’, ‘Niko’/ Phenomenal™, and ‘Sharon Roberts’. Phenomenal™ was the only top-performing non-angustifolia type.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Royal Velvet’Long-blooming ‘Royal Velvet’ featured dark lavender flowers with dark purple calyces from late June to late September. Graygreen leaves formed neat mounds to 14 inches tall and 40 inches wide—tall floral stems rose nearly a foot above the foliage. ‘Royal Velvet’ showed exceptional cold hardiness, suffering only moderate stem injury in one out of five winters.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Imperial Gem’‘Imperial Gem’ was a superior lavender in all respects—free-flowering, robust, and cold-hardy. The dark lavender flowers with dark purple calyces bloomed from late June to mid-September. It featured graygreen leaves and a dense mounded habit, 22 inches tall with flowers and 45 inches wide after six years. ‘Imperial Gem’ was consistently the top-performing lavender every year of the trial.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Munstead’‘Munstead’ and ‘Hidcote’ are popular and widely grown lavenders; however, ‘Munstead’ exhibited greater cold hardiness than ‘Hidcote’, with no plants dying over winter. Featuring lavender-blue flowers with dark purple calyces and silvery green leaves, ‘Munstead’ was a dependable performer during its six years in the garden. At 56 inches wide, it was among the largest of the lavenders. Both cultivars are commonly seed-grown, which accounts for the slight variations we observed among the plants.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘SuperBlue’‘SuperBlue’ was the most compact lavender, reaching just 10 inches tall and 15 inches wide after four years. It was naturally the smallest of the healthy lavenders— plants that did not thrive such as ‘Ellagance Purple’ and ‘Martha Roderick’ were typically smaller. Its dark lavender flowers complemented the silvery green leaves for several months. The dense flower spikes had fewer gaps than most cultivars, which made for an intense color show. Winter hardiness was not a problem for ‘SuperBlue’, with minor stem injury noted only in 2013– 2014.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Jean Davis’‘Jean Davis’ was not the only pink-flowered lavender tested, but it was far superior to the others. The pale pink to pinkish white flowers were borne in profusion from late June to mid-August. Plants topped out at 24 inches tall with flowers and 42 inches wide. ‘Jean Davis’ was reliably hardy throughout the six-year trial; moderate stem injury occurred in just one winter. In a sea of lavender, the soft pink flowers of ‘Jean Davis’ were a standout.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Sharon Roberts’The lavender-blue flowers of ‘Sharon Roberts’ were slightly larger than typical of most lavenders, and bloomed freely from late June to early September. Size comes with age and after six years, the plants were 52 inches wide and 14 inches tall— the flower stems nearly doubled the height. Despite significant stem loss in one winter, plant health and habit quality rebounded quickly the following summer. The superior cold hardiness and vigorous nature of ‘Sharon Roberts’ contributed to its larger plant size.

Lavandula xintermedia

‘Niko’/ Phenomenal™The lavandin cultivars were generally not as cold-hardy as English lavender; however, ‘Niko’ performed significantly better than the other cultivars and comparable to an English lavender. No stem injury was noted during four winters in the trial, but one plant died in the winter of 2014–15. Phenomenal ™ had a uniform mounding habit, with floral stems standing well above the silvery green leaves. While it had a similar look to the other lavandins, it was the shortest at 22 inches tall. Lavender-blue flowers were plentiful from late June to late September.

Seven taxa received the highest ratings for exceptional flower production, healthy foliage, vigorous habits, adaptability to the growing conditions, and superior winter hardiness. Based on cumulative evaluation scores, the top-rated lavenders in descending order were ‘Imperial Gem’, ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Munstead’, ‘SuperBlue’, ‘Jean Davis’, ‘Niko’/ Phenomenal™, and ‘Sharon Roberts’. Phenomenal™ was the only top-performing non-angustifolia type.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Royal Velvet’Long-blooming ‘Royal Velvet’ featured dark lavender flowers with dark purple calyces from late June to late September. Graygreen leaves formed neat mounds to 14 inches tall and 40 inches wide—tall floral stems rose nearly a foot above the foliage. ‘Royal Velvet’ showed exceptional cold hardiness, suffering only moderate stem injury in one out of five winters.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Imperial Gem’‘Imperial Gem’ was a superior lavender in all respects—free-flowering, robust, and cold-hardy. The dark lavender flowers with dark purple calyces bloomed from late June to mid-September. It featured graygreen leaves and a dense mounded habit, 22 inches tall with flowers and 45 inches wide after six years. ‘Imperial Gem’ was consistently the top-performing lavender every year of the trial.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Munstead’‘Munstead’ and ‘Hidcote’ are popular and widely grown lavenders; however, ‘Munstead’ exhibited greater cold hardiness than ‘Hidcote’, with no plants dying over winter. Featuring lavender-blue flowers with dark purple calyces and silvery green leaves, ‘Munstead’ was a dependable performer during its six years in the garden. At 56 inches wide, it was among the largest of the lavenders. Both cultivars are commonly seed-grown, which accounts for the slight variations we observed among the plants.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘SuperBlue’‘SuperBlue’ was the most compact lavender, reaching just 10 inches tall and 15 inches wide after four years. It was naturally the smallest of the healthy lavenders— plants that did not thrive such as ‘Ellagance Purple’ and ‘Martha Roderick’ were typically smaller. Its dark lavender flowers complemented the silvery green leaves for several months. The dense flower spikes had fewer gaps than most cultivars, which made for an intense color show. Winter hardiness was not a problem for ‘SuperBlue’, with minor stem injury noted only in 2013– 2014.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Jean Davis’‘Jean Davis’ was not the only pink-flowered lavender tested, but it was far superior to the others. The pale pink to pinkish white flowers were borne in profusion from late June to mid-August. Plants topped out at 24 inches tall with flowers and 42 inches wide. ‘Jean Davis’ was reliably hardy throughout the six-year trial; moderate stem injury occurred in just one winter. In a sea of lavender, the soft pink flowers of ‘Jean Davis’ were a standout.

Lavandula angustifolia

‘Sharon Roberts’The lavender-blue flowers of ‘Sharon Roberts’ were slightly larger than typical of most lavenders, and bloomed freely from late June to early September. Size comes with age and after six years, the plants were 52 inches wide and 14 inches tall— the flower stems nearly doubled the height. Despite significant stem loss in one winter, plant health and habit quality rebounded quickly the following summer. The superior cold hardiness and vigorous nature of ‘Sharon Roberts’ contributed to its larger plant size.

Lavandula xintermedia

‘Niko’/ Phenomenal™The lavandin cultivars were generally not as cold-hardy as English lavender; however, ‘Niko’ performed significantly better than the other cultivars and comparable to an English lavender. No stem injury was noted during four winters in the trial, but one plant died in the winter of 2014–15. Phenomenal ™ had a uniform mounding habit, with floral stems standing well above the silvery green leaves. While it had a similar look to the other lavandins, it was the shortest at 22 inches tall. Lavender-blue flowers were plentiful from late June to late September.

-

Winter Hardiness

Winter hardiness, defined as adaptability to cold temperatures, was measured by the degree of stem and/or crown injury observed, ranging from none to plant death. Winter injury varied by taxon and by year, but all lavenders sustained some degree of injury in one or more years (see Table 3). The majority of stem injuries and plant losses occurred in the winters of 2013, 2014, and 2015, which correlates to the lowest recorded temperatures and the most days below zero during the trial period. In fact, the greatest number of taxa—32 out of 37, or 86 percent— suffered moderate to severe crown injury and/or loss of one or all plants per taxon in the winter of 2013–14; subzero temperatures were logged on 24 days between early January and mid-February and the lowest temperature recorded was minus 16 degrees Fahrenheit on January 6. Significant rates of stem injury and plant losses were noted in other winters, ranging from 58 percent in 2014–15 to 43 percent in 2012–13. Only 3 percent of taxa died in the mild winter of 2011–12; however, despite being the only winter during the trial with no recorded subzero temperatures, 41 percent of plants had moderate to severe stem injury.

The influence of snow cover on stem hardiness was an important consideration in the trial. Snow cover was recorded at ≥6 inches on all subzero dates in 2010-11, 2013-14 and 2014-15; snow depth in the winter of 2013-14 averaged 15 inches on all days with negative temperatures. Comparable snow cover measurements were noted in 2010-11 and 2014- 15, but there was no snow present on the coldest day—minus 3 degrees Fahrenheit—in January 2013. Based on stem injury and plant loss assessments for all winters, it does not appear that snow provided a significant insulating effect for the lavenders during severely cold temperatures. However, snow depth averaged 13 inches in January 2012 when the lowest temperature of the winter was 2 degrees Fahrenheit, so it is possible that adequate snow cover combined with milder temperatures improved crown survival. As previously noted, stem damage was significant but only 3 percent of plants died that winter.

Standard evaluation protocol is to replace plants that die in the first or second year of a trial, whether from cultural or environmental causes. Five taxa were retrialed because the original plants died in winter; all plants of ‘Ellagance Sky’, ‘Grappenhall’, ‘Grosso’, ‘Martha Roderick’, and ‘Schola’ were replaced once (see Table 3). Several taxa had duplicate accessions growing concurrently in the trial including ‘Hidcote Superior’, Lavance Purple®, ‘Mitcham Gray’, and ‘Thumbelina Leigh’. With the exception of ‘Thumbelina Leigh’, the other three taxa were proactive replacements for anticipated winter injury based on the previous year’s performance rather than actual losses.

Cultural and Environmental Adaptability

Lavenders prefer well-drained to dry soils for optimum growth; thus, wet soils for extended periods can lead to poor health or plant death. Given that our trial beds retained excess moisture for short periods in summer and winter, the adaptability of the lavenders to periodic or sustained soil moisture was as important to survivability as cold hardiness. Newly planted lavenders seemed more sensitive to prolonged wet conditions compared to well-established plants, but older plants occasionally declined due to poor drainage during the growing season.

Among the taxa with declining health and/or death of one or more plants in their first summer were ‘Blue River’, ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Ellagance Ice’, ‘Ellagance Purple’, ‘Ellagance Sky’, ‘Grappenhall’, ‘Hidcote’, ‘Irene Doyle’, ‘Kerlavangem’/Sweet Romance™, ‘Martha Roderick’, ‘Melissa’, ‘Sarah’, and ‘Victorian Amethyst’. In all cases, plants were healthy and robust when planted in June but their health deteriorated during the summer months from prolonged wet conditions. Following two unsuccessful attempts to establish ‘Sarah’ in the 2010 and 2011 growing seasons, plants finally survived the third planting in spring 2012 and were successfully overwintered for a few years.

A number of established lavenders experienced significant and sustained health issues attributed to wet soils, which resulted in a decline in plant health and/or plant death; the affected taxa included ‘Blue River’, Lavance Purple®, ‘Miss Katherine’, ‘Mitcham Gray’, ‘Schola’, ‘Vera’ and ‘Victorian Amethyst’. These lavenders in particular were determined to be the least adaptable to wet soils, whether periodic or prolonged.

There were no confirmed diseases on the lavenders during the trial period; yet, symptoms similar to Phyllosticta blight and Fusarium wilt were observed on ‘Blue River’, ‘Buena Vista’, ‘Ellagance Ice’, Lavance Purple®, and ‘Victorian Amethyst’ at various times during the trial. Spider mites infested plants of ‘Blue River’ and ‘Ellagance Ice’ in July 2012 only.

Ornamental Attributes

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Dwarf Blue’

The baseline description of an ornamentally exceptional lavender was one with a robust, well-formed habit; high flower production and full crown coverage; and healthy, clean foliage. Specifically, data was collected on flower production including uniformity of coverage on the plant, length of bloom period, flower size, blossom and calyx colors, leaf color, and floral stem architecture and fullness of habit. The speed and extent that a plant rebounded from winter injury was assessed as well. Although important from an ornamental standpoint, non-quantifiable, subjective attributes such as flower color and leaf color were not factored into the overall rating.

Each of the top-ranked lavenders received a good-excellent rating, i.e. four and a half stars out of five, for their superior ornamental displays. ‘Imperial Gem’, ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Super- Blue’, ‘Jean Davis’, ‘Sharon Roberts’, and ‘Niko’/ Phenomenal™ were consistently heavy bloomers, and exhibited full, robust plant habits due in part to minimal stem injury in winter.

As a color, lavender is light purple but it also applies to a wide range of pale to grayish purple colors including light magenta and light violet. Color designations can vary widely since the perception of color, and ultimately its naming, is particular to the viewer. Flower colors for the taxa in the trial generally ranged from light to dark violet as well as pink and white. A flower color designation of lavender in Table 2 denotes a moderate violet shade. Whether lighter, darker, or similarly hued, the color of the calyx complemented the flower color and was an important part of the floral description. Moreover, the calyx was colorful before flowers opened, and remained vibrant for a time after the flowers dropped, effectively extending the floral display for several weeks or longer.

Lavandula xintermedia ‘Provence'

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Violet Intrigue’

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Thumbelina Leigh’

A classic peak bloom was not obvious; lavender flowers opened sporadically and were not necessarily present in large quantities at any time on an inflorescence. Flower production during the bloom period noted in Table 2 was measured as the percentage of inflorescences with open flowers, rather than the percentage of open flowers per inflorescence. In light of this intermittent flowering habit, a calyx color that enhanced the floral display was especially notable, such as the dark purple calyces of ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Imperial Gem’, and ‘SuperBlue’. Individual flowers were small—the majority measured ¼ inch wide across the lower lip, although ‘French Perfume’ had the largest flowers at 3/8 inch wide. Flowers were clustered in short spikes, 2 to 3 inches long, at the ends of stiff floral stems above the foliage. Lavandula angustifolia ‘Graves’ and L. xintermedia ‘Provence’ had the tallest flower stems at 18 inches and 20 inches, respectively. In the case of ‘Graves’ and L. xintermedia ‘Gros Bleu’, flower stems were green, which was a novelty compared to the typically gray-green stems of other lavenders.

Leaves were generally gray-green to silvery green— there was no strong distinction between the foliage colors of the various lavenders. However, Walberton’s® Arctic Fox featured gray-green leaves with creamy silver margins. Foliage quality was consistently good on healthy lavenders year after year. Winter- desiccated leaves typically held onto living stems into summer. If not removed, the withered foliage eventually dropped off or was masked by new growth, which typically began in May or early June and eventually filled in dead areas by late June.

Initially, most of the English lavenders had compact, rounded habits, but over time, some of the oldest plants became more sprawling, reaching nearly 5 feet wide. Plant height to the top of the leaves ranged between 10 and 20 inches. Flower stems from several inches to 20 inches long rose above the leaves, in some cases increasing plant height considerably. Among the largest plants in height and width were Lavandula angustifolia ‘Graves’ and L. xintermedia ‘Provence’. Because of their tall floral stems, both lavenders featured the greatest separation between foliar mounds and flower spikes. Phenomenal™ (L. xintermedia ‘Niko’) had a similar appearance but on a smaller scale.

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Loddon Blue’

Winter stem dieback resulted in loose, open, and/or lopsided plants, and typically, reduced flower production. Inferior habits due to winter injury were a major factor in the low ornamental ratings for some lavenders such as Lavance Purple®, ‘Victorian Amethyst’, and ‘Grosso’. A lavender’s ability to rebound quickly and vigorously after sustaining stem injury greatly influenced its habit quality rating. Despite occasionally severe stem dieback, vigorous spring growth and strong flower production contributed to higher ratings for ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Loddon Blue’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Sharon Roberts’, and ‘Violet Intrigue’. Lavandula angustifolia ‘Graves’ and L. xchaytoriae ‘Richard Gray’ would have received higher ornamental ratings if not for significant stem injury and/ or plant losses. Contrary to our usual hands-off maintenance regimen, we removed dead stems after winter injury assessment to promote growth and to improve habit quality.

Winter Hardiness

Winter hardiness, defined as adaptability to cold temperatures, was measured by the degree of stem and/or crown injury observed, ranging from none to plant death. Winter injury varied by taxon and by year, but all lavenders sustained some degree of injury in one or more years (see Table 3). The majority of stem injuries and plant losses occurred in the winters of 2013, 2014, and 2015, which correlates to the lowest recorded temperatures and the most days below zero during the trial period. In fact, the greatest number of taxa—32 out of 37, or 86 percent— suffered moderate to severe crown injury and/or loss of one or all plants per taxon in the winter of 2013–14; subzero temperatures were logged on 24 days between early January and mid-February and the lowest temperature recorded was minus 16 degrees Fahrenheit on January 6. Significant rates of stem injury and plant losses were noted in other winters, ranging from 58 percent in 2014–15 to 43 percent in 2012–13. Only 3 percent of taxa died in the mild winter of 2011–12; however, despite being the only winter during the trial with no recorded subzero temperatures, 41 percent of plants had moderate to severe stem injury.

The influence of snow cover on stem hardiness was an important consideration in the trial. Snow cover was recorded at ≥6 inches on all subzero dates in 2010-11, 2013-14 and 2014-15; snow depth in the winter of 2013-14 averaged 15 inches on all days with negative temperatures. Comparable snow cover measurements were noted in 2010-11 and 2014- 15, but there was no snow present on the coldest day—minus 3 degrees Fahrenheit—in January 2013. Based on stem injury and plant loss assessments for all winters, it does not appear that snow provided a significant insulating effect for the lavenders during severely cold temperatures. However, snow depth averaged 13 inches in January 2012 when the lowest temperature of the winter was 2 degrees Fahrenheit, so it is possible that adequate snow cover combined with milder temperatures improved crown survival. As previously noted, stem damage was significant but only 3 percent of plants died that winter.

Standard evaluation protocol is to replace plants that die in the first or second year of a trial, whether from cultural or environmental causes. Five taxa were retrialed because the original plants died in winter; all plants of ‘Ellagance Sky’, ‘Grappenhall’, ‘Grosso’, ‘Martha Roderick’, and ‘Schola’ were replaced once (see Table 3). Several taxa had duplicate accessions growing concurrently in the trial including ‘Hidcote Superior’, Lavance Purple®, ‘Mitcham Gray’, and ‘Thumbelina Leigh’. With the exception of ‘Thumbelina Leigh’, the other three taxa were proactive replacements for anticipated winter injury based on the previous year’s performance rather than actual losses.

Cultural and Environmental Adaptability

Lavenders prefer well-drained to dry soils for optimum growth; thus, wet soils for extended periods can lead to poor health or plant death. Given that our trial beds retained excess moisture for short periods in summer and winter, the adaptability of the lavenders to periodic or sustained soil moisture was as important to survivability as cold hardiness. Newly planted lavenders seemed more sensitive to prolonged wet conditions compared to well-established plants, but older plants occasionally declined due to poor drainage during the growing season.

Among the taxa with declining health and/or death of one or more plants in their first summer were ‘Blue River’, ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Ellagance Ice’, ‘Ellagance Purple’, ‘Ellagance Sky’, ‘Grappenhall’, ‘Hidcote’, ‘Irene Doyle’, ‘Kerlavangem’/Sweet Romance™, ‘Martha Roderick’, ‘Melissa’, ‘Sarah’, and ‘Victorian Amethyst’. In all cases, plants were healthy and robust when planted in June but their health deteriorated during the summer months from prolonged wet conditions. Following two unsuccessful attempts to establish ‘Sarah’ in the 2010 and 2011 growing seasons, plants finally survived the third planting in spring 2012 and were successfully overwintered for a few years.

A number of established lavenders experienced significant and sustained health issues attributed to wet soils, which resulted in a decline in plant health and/or plant death; the affected taxa included ‘Blue River’, Lavance Purple®, ‘Miss Katherine’, ‘Mitcham Gray’, ‘Schola’, ‘Vera’ and ‘Victorian Amethyst’. These lavenders in particular were determined to be the least adaptable to wet soils, whether periodic or prolonged.

There were no confirmed diseases on the lavenders during the trial period; yet, symptoms similar to Phyllosticta blight and Fusarium wilt were observed on ‘Blue River’, ‘Buena Vista’, ‘Ellagance Ice’, Lavance Purple®, and ‘Victorian Amethyst’ at various times during the trial. Spider mites infested plants of ‘Blue River’ and ‘Ellagance Ice’ in July 2012 only.

Ornamental Attributes

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Dwarf Blue’

The baseline description of an ornamentally exceptional lavender was one with a robust, well-formed habit; high flower production and full crown coverage; and healthy, clean foliage. Specifically, data was collected on flower production including uniformity of coverage on the plant, length of bloom period, flower size, blossom and calyx colors, leaf color, and floral stem architecture and fullness of habit. The speed and extent that a plant rebounded from winter injury was assessed as well. Although important from an ornamental standpoint, non-quantifiable, subjective attributes such as flower color and leaf color were not factored into the overall rating.

Each of the top-ranked lavenders received a good-excellent rating, i.e. four and a half stars out of five, for their superior ornamental displays. ‘Imperial Gem’, ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Super- Blue’, ‘Jean Davis’, ‘Sharon Roberts’, and ‘Niko’/ Phenomenal™ were consistently heavy bloomers, and exhibited full, robust plant habits due in part to minimal stem injury in winter.

As a color, lavender is light purple but it also applies to a wide range of pale to grayish purple colors including light magenta and light violet. Color designations can vary widely since the perception of color, and ultimately its naming, is particular to the viewer. Flower colors for the taxa in the trial generally ranged from light to dark violet as well as pink and white. A flower color designation of lavender in Table 2 denotes a moderate violet shade. Whether lighter, darker, or similarly hued, the color of the calyx complemented the flower color and was an important part of the floral description. Moreover, the calyx was colorful before flowers opened, and remained vibrant for a time after the flowers dropped, effectively extending the floral display for several weeks or longer.

Lavandula xintermedia ‘Provence'

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Violet Intrigue’

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Thumbelina Leigh’

A classic peak bloom was not obvious; lavender flowers opened sporadically and were not necessarily present in large quantities at any time on an inflorescence. Flower production during the bloom period noted in Table 2 was measured as the percentage of inflorescences with open flowers, rather than the percentage of open flowers per inflorescence. In light of this intermittent flowering habit, a calyx color that enhanced the floral display was especially notable, such as the dark purple calyces of ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Imperial Gem’, and ‘SuperBlue’. Individual flowers were small—the majority measured ¼ inch wide across the lower lip, although ‘French Perfume’ had the largest flowers at 3/8 inch wide. Flowers were clustered in short spikes, 2 to 3 inches long, at the ends of stiff floral stems above the foliage. Lavandula angustifolia ‘Graves’ and L. xintermedia ‘Provence’ had the tallest flower stems at 18 inches and 20 inches, respectively. In the case of ‘Graves’ and L. xintermedia ‘Gros Bleu’, flower stems were green, which was a novelty compared to the typically gray-green stems of other lavenders.

Leaves were generally gray-green to silvery green— there was no strong distinction between the foliage colors of the various lavenders. However, Walberton’s® Arctic Fox featured gray-green leaves with creamy silver margins. Foliage quality was consistently good on healthy lavenders year after year. Winter- desiccated leaves typically held onto living stems into summer. If not removed, the withered foliage eventually dropped off or was masked by new growth, which typically began in May or early June and eventually filled in dead areas by late June.

Initially, most of the English lavenders had compact, rounded habits, but over time, some of the oldest plants became more sprawling, reaching nearly 5 feet wide. Plant height to the top of the leaves ranged between 10 and 20 inches. Flower stems from several inches to 20 inches long rose above the leaves, in some cases increasing plant height considerably. Among the largest plants in height and width were Lavandula angustifolia ‘Graves’ and L. xintermedia ‘Provence’. Because of their tall floral stems, both lavenders featured the greatest separation between foliar mounds and flower spikes. Phenomenal™ (L. xintermedia ‘Niko’) had a similar appearance but on a smaller scale.

Lavandula angustifolia ‘Loddon Blue’

Winter stem dieback resulted in loose, open, and/or lopsided plants, and typically, reduced flower production. Inferior habits due to winter injury were a major factor in the low ornamental ratings for some lavenders such as Lavance Purple®, ‘Victorian Amethyst’, and ‘Grosso’. A lavender’s ability to rebound quickly and vigorously after sustaining stem injury greatly influenced its habit quality rating. Despite occasionally severe stem dieback, vigorous spring growth and strong flower production contributed to higher ratings for ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Loddon Blue’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Sharon Roberts’, and ‘Violet Intrigue’. Lavandula angustifolia ‘Graves’ and L. xchaytoriae ‘Richard Gray’ would have received higher ornamental ratings if not for significant stem injury and/ or plant losses. Contrary to our usual hands-off maintenance regimen, we removed dead stems after winter injury assessment to promote growth and to improve habit quality.

-

There were two noteworthy consequences of undertaking and completing the lavender trial. Most importantly, the outcome, whether positive or negative, is informative to gardeners beyond simply anecdotal. Additionally, discovering a variety of adaptable lavenders diversifies the offerings for northern gardens. Of the 40 lavenders trialed between 2010 and 2016, thirteen selections—representing a good variety of flower colors and plant sizes—received high ratings for their overall performances. Besides robust habits and superior floral displays, these lavenders proved winter Lavandula angustifolia ‘Dwarf Blue’ hardy and adaptable to the challenging growing conditions of the trial site. The thirteen top-rated lavenders included ‘Imperial Gem’, ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Super- Blue’, ‘Jean Davis’, ‘Niko’/Phenomenal™, ‘Sharon Roberts’, ‘Violet Intrigue’, ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Loddon Blue’, ‘Thumbelina Leigh’, ‘Oxford Gem’, and ‘Irene Doyle’.

Cold hardiness and adaptability to wet clay soils were the primary concerns at the outset of the trial. Both criteria were challenges to successfully growing lavenders, and at times, it was uncertain whether one was more detrimental than the other was. While not proven in all cases, the lavenders that struggled to survive the growing conditions were more susceptible to injury from cold temperatures. Longevity was not conclusively determined but the top performers survived and excelled for the duration of their time in the trial, which in many instances was five or six years.

All lavenders sustained some level of injury in one or more winters, although damage varied by lavender and by year. There was a direct correlation between the degree of winter stem loss and habit quality and flower production; that is, lavenders with the least amount of stem injury looked the best. A number of lavenders, such as ‘Hidcote Superior’, Lavance Purple®, and ‘Mitcham Gray’, were strong performers early in their trial, but were not able to recover fully after suffering significant winter injuries.

The flower shows provided by the lavenders were quite good overall. The majority of lavenders produced copious flowers, and were ornamental for a protracted period because of the long-lasting color of the calyces. Longer floral stalks created a more dramatic flower show, which was especially notable on lavandin selections such as ‘Gros Bleu’, ‘Niko’/Phenomenal™, and ‘Provence’. Plants were not deadheaded in the trial but it was clear that removing aging flower stems would improve the ornamental display. Winter-dead stems were removed after new growth began in spring in an effort to improve habit quality.

Through formal comparative evaluation, we realized our goal of identifying a variety of lavenders adaptable to colder regions and average to challenging growing conditions. In the end, a third of the lavenders garnered at least four out of five stars; these successes will provide greater certainty when selecting a lavender for northern gardens.

There were two noteworthy consequences of undertaking and completing the lavender trial. Most importantly, the outcome, whether positive or negative, is informative to gardeners beyond simply anecdotal. Additionally, discovering a variety of adaptable lavenders diversifies the offerings for northern gardens. Of the 40 lavenders trialed between 2010 and 2016, thirteen selections—representing a good variety of flower colors and plant sizes—received high ratings for their overall performances. Besides robust habits and superior floral displays, these lavenders proved winter Lavandula angustifolia ‘Dwarf Blue’ hardy and adaptable to the challenging growing conditions of the trial site. The thirteen top-rated lavenders included ‘Imperial Gem’, ‘Royal Velvet’, ‘Munstead’, ‘Super- Blue’, ‘Jean Davis’, ‘Niko’/Phenomenal™, ‘Sharon Roberts’, ‘Violet Intrigue’, ‘Dwarf Blue’, ‘Loddon Blue’, ‘Thumbelina Leigh’, ‘Oxford Gem’, and ‘Irene Doyle’.

Cold hardiness and adaptability to wet clay soils were the primary concerns at the outset of the trial. Both criteria were challenges to successfully growing lavenders, and at times, it was uncertain whether one was more detrimental than the other was. While not proven in all cases, the lavenders that struggled to survive the growing conditions were more susceptible to injury from cold temperatures. Longevity was not conclusively determined but the top performers survived and excelled for the duration of their time in the trial, which in many instances was five or six years.

All lavenders sustained some level of injury in one or more winters, although damage varied by lavender and by year. There was a direct correlation between the degree of winter stem loss and habit quality and flower production; that is, lavenders with the least amount of stem injury looked the best. A number of lavenders, such as ‘Hidcote Superior’, Lavance Purple®, and ‘Mitcham Gray’, were strong performers early in their trial, but were not able to recover fully after suffering significant winter injuries.

The flower shows provided by the lavenders were quite good overall. The majority of lavenders produced copious flowers, and were ornamental for a protracted period because of the long-lasting color of the calyces. Longer floral stalks created a more dramatic flower show, which was especially notable on lavandin selections such as ‘Gros Bleu’, ‘Niko’/Phenomenal™, and ‘Provence’. Plants were not deadheaded in the trial but it was clear that removing aging flower stems would improve the ornamental display. Winter-dead stems were removed after new growth began in spring in an effort to improve habit quality.

Through formal comparative evaluation, we realized our goal of identifying a variety of lavenders adaptable to colder regions and average to challenging growing conditions. In the end, a third of the lavenders garnered at least four out of five stars; these successes will provide greater certainty when selecting a lavender for northern gardens.